148 Łukasz Damurski, Magdalena Olszyna, Jan Zipser

State of research

What is neighbourhood cohesion?

Wherever there is life, there is a deep-rooted purpose,

represented by functionality, a high level of organization,

coherence, and harmony in all animate beings (Çengel

2023). Hence, some kind of cohesion is a fundamental cha -

racteristic of all living systems. This statement can be also

applied to urban neighbourhoods, which are characterised

by a hierarchical structure of places performing dierent

functions, with a certain degree of self-suciency and

evolv ing over time. Originally developed in psychology,

so ciology, anthropology and biology (Buckner 1988), the

con cept of neighbourhood cohesion has recently been ap-

plied to territorial governance (Damurski 2022), thus ac-

quiring a tangible spatial dimension.

The original concept of neighbourhood cohesion was

an amalgamation of several approaches within the social

and psychological sciences. It was introduced as a synthe-

sis of a psychological sense of community, attraction to

the neighbourhood and social interaction within the neigh-

bourhood. It was assumed that residents living in a neigh-

bourhood had a certain degree of cohesion, which implied

a certain embeddedness of residents in a particular space

and positive (functional) social ties in the community.

In its extended version, neighbourhood cohesion is

a unique set of interrelated geographical and social charac-

teristics, and it depends on the perceived functional self-su-

ciency of a neighbourhood, the accessibility of essential ser-

vices (both public and private), and the relationship between

supply and demand observed in a given area (Damurski

2022). Therefore, an important strand of neighbourhood co-

hesion is citizens’ access to public infrastructure and services.

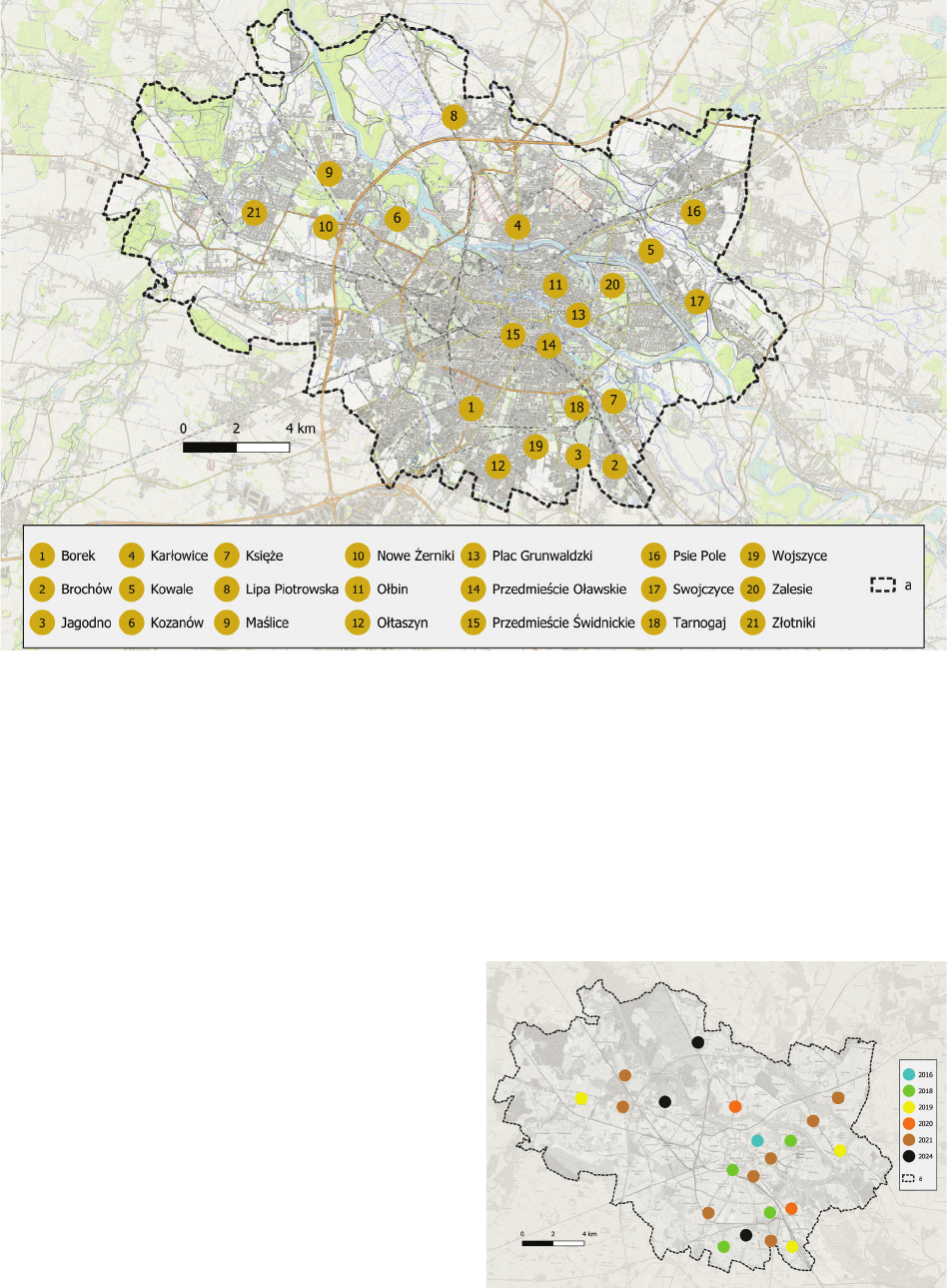

In this paper, a particular type of services has been se-

lected and examined in order to explore the neighbourhood

cohesion in Wrocław: the Local Activity Centres. On the

one hand, they can be perceived as an element of the for-

mally established public services system, lling important

gaps in the municipally-driven network of facilities ded-

icated to social integration, local culture, education, and

recreation. On the other hand though, they are a grassroots

initiatives, initiated and driven by the local leaders, in-

volved in the everyday life of local communities in partic-

ular neighbourhoods. This dual character of LACs – both

top-down and bottom-up – makes them a very interesting

example of urban services and as such it may have a signif-

icant role to play in shaping the neighbourhood cohesion

in Wrocław.

Community centre: the prototype

of the local activity centre

The rst community centres were established in the

United Kingdom in late 19

th

century, but now they can be

found all over Europe, the United States of America and

even in Asia. Community centres are public spaces that

serve as places for meeting, support, and activity for local

communities. They oer a variety of services and program-

mes, such as educational, recreational, cultural, as well as

social and health support. They are managed by local au

-

thorities, non-governmental organizations (NGO) or vol-

unteer groups and aim to strengthen social ties, promote

inclusion and improve the quality of life in the community

(Mayo, Mendiwelso-Bendek and Packham 2013).

According to the concept of the “modern agora” pro-

moted by Frank van Klingeren in the 1960s and 1970s,

a neighbourhood centre is meant to be a place of social

integration, enabling the exchange of knowledge and the

cultivation of diverse activities and interests. The function-

al and spatial programme of such a space is not dedicated

to a specic group of people – rather it should be open,

exible, and adaptable to the current needs of dierent us-

ers over the course of a day, week, month and year (Kowic-

ki 2004).

In the United Kingdom, many villages and towns have

their own community centres, although nearby schools

may also provide their lecture halls or canteens for af-

ter-school activities. In other parts of the world, commu-

nity centres may play many dierent roles, including civic

engagement (e.g., discussion on local governance issues

or disaster prevention), culture and leisure (e.g., organiz-

ing local cultural events, hobby classes, physical exercise

activities, exhibitions), citizen education (e.g., lectures on

history and culture, youth classes, library), assistance to

residents (e.g., provision of everyday life information, sport

and tness training sessions, ea markets, supporting the

vulnerable groups, welfare and health improvement) and

community development (e.g., public areas cleaning, mutu-

al assistance, youth guidance) (developed after Eun 2010).

All those activities can be conducted in a dedicated place,

equipped with particular facilities, or can be organized on

a temporary basis in schools, parishes, or sports centres.

In Poland, the traditional counterpart of a community

centre is the “house of culture” (dom kultury). The ori-

gins of the concept date back to the 18

th

century, when the

rst initiatives aimed at promoting education and culture

among the rural population emerged. In the 19

th

century,

the dominant cultural institutions were public reading

rooms and various socio-cultural associations, which de-

veloped under the inuence of the idea of grassroots work

and positivism. In the interwar period, the number of hous-

es of culture increased signicantly, and their aim was to

reduce the barriers in access to culture and to blur the dif-

ferences between elite and popular culture. In the times of

the People’s Republic of Poland, cultural centres became

a key tool in the hands of the authorities, serving as places

of propaganda accessible to the broad masses. After the

political transformation at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s,

the function and form of cultural centres changed again,

adapting to the new social and political realities (Zoom Na

Domy Kultury 2024).

Today, houses of culture are local government institu-

tions which, unlike artistic institutions, libraries and muse-

ums, are not only supposed to organise cultural events, but

also to work for the integration of local communities and

to carry out animation and educational activities. There-

fore, they have a special status among cultural institu-

tions, resulting from the type of activities they undertake

(Wiśniewski, Rydzewski 2022).