The Luzi House by Peter Zumthor as an archetype for the synthesis of tradition and innovation in rural areas 43

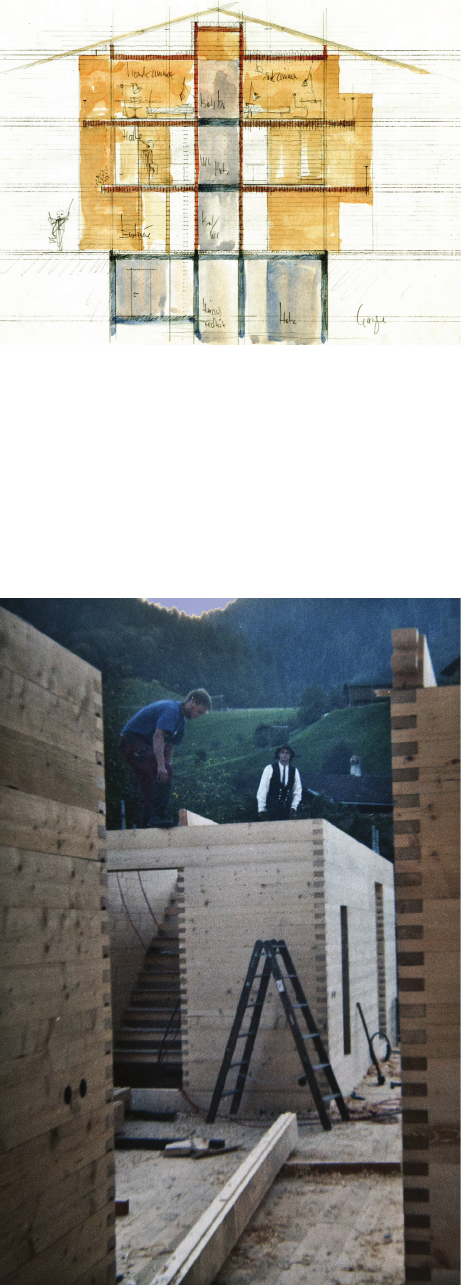

had to be given special consideration (Zumthor, Bachmann

2000, 221). While Zumthor and his colleagues assumed

a height loss of around 3 cm per oor for the rst few

years, a lower height loss was expected for the following

years (Durisch 2014a, 133). In order to react to the result-

ing movements of the wood and also to achieve a certain

degree of insulation protection, joints approximately 1 cm

wide were provided at the transitions from oor to wall

and around the door frames. Similar to the Gugalun House,

where Zumthor – as Truog emphasized – had deliberately

decided against covering up inaccuracies in the processing

of the wood with skirting boards and instead paid attention

to the exact dimensions of the walls, a satisfactory result

only seemed achievable here too through close collabora-

tion between architects, structural engineers and craftsmen

as well as precise and conscientious craftsmanship.

Methods

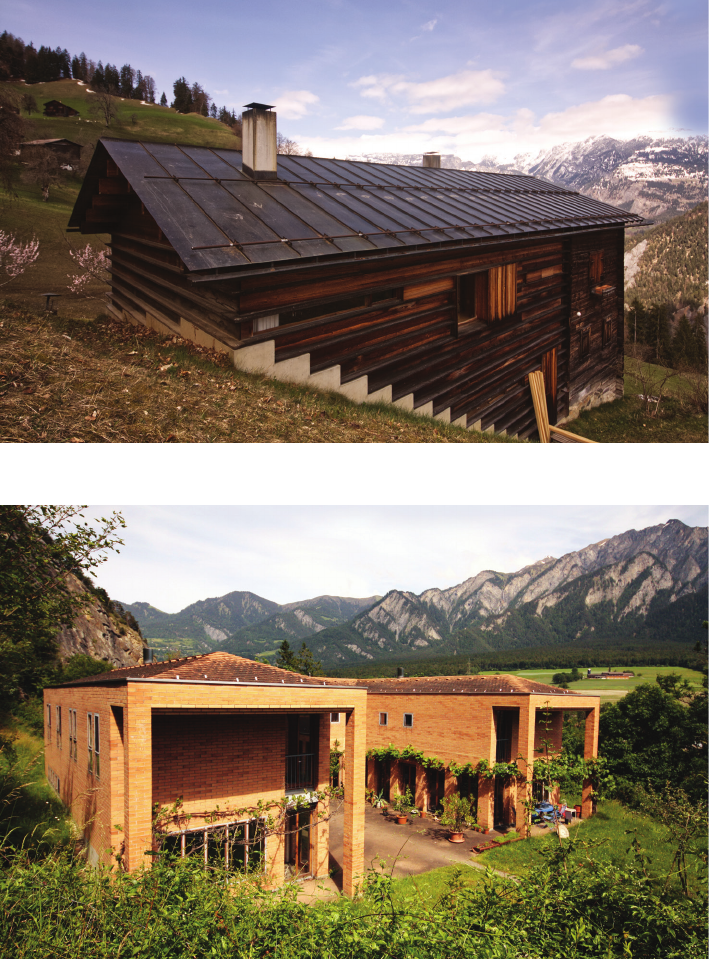

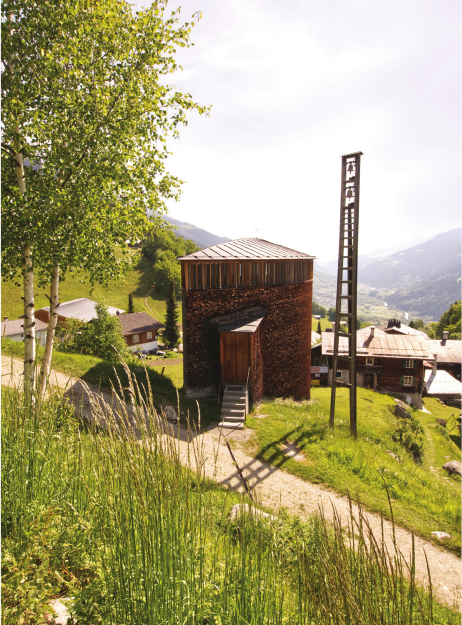

Despite its modern interpretation of a wooden house,

the overall appearance of the house appears to blend in

well with the topography, the village building structure

and the agricultural character of the region, and to connect

with the buildings, meadows, gardens, fences and paths of

Graubünden (Fig. 8) (Durisch 2014b, 34). Similar to the

architect’s own house, the form here was also intended to

counteract the simple, rustic Alpine style that was wide-

spread in new buildings at the time, and instead function

as a sign of clarity and calm. The house thus embodies an

architecture that picks up on the basic sound of the land-

scape and houses that has evolved over centuries (Durisch

2014b, 57). This eect can be attributed not only to the

use of a classic structure with a rectangular oor plan and

a gabled roof, but above all to the materiality of the wood

used. On the one hand, it defends itself against nature, but

on the other hand it also reveals itself to be part of nature,

as sunlight, rain, splashing water, temperature uctuations

and dirt leave their mark on it. Depending on their position

and orientation, the surfaces made of spruce beams have

a warm reddish or cold greyish colour and thus reinforce

the vitality of the surfaces already achieved by the grain of

the wood, which creates a contrast to the overall construc-

tion, which is committed to strictly geometric forms, the

linear structure of the layering created by the beams and

the shape of individual elements such as windows, doors

and the vertical and horizontal wall and ceiling panes pro-

truding from the façade, which emphasize the right angles.

The prevention of direct weathering on the east façade by

the roof and the open walls, combined with the lack of di-

rect exposure to sunlight, has preserved the original colour

of the wood in places, whereas more exposed areas, such

as the splash water area, are characterized by a greyish co-

lour. If one interprets such appearances as an expression

of ageing processes, a connection to the other older farm-

houses that characterize the village emerges. The graceful-

ly ageing appearance of the Luzi House leads to it being

recognized as having a comparable connection to the earth

and a place within the history of the village.

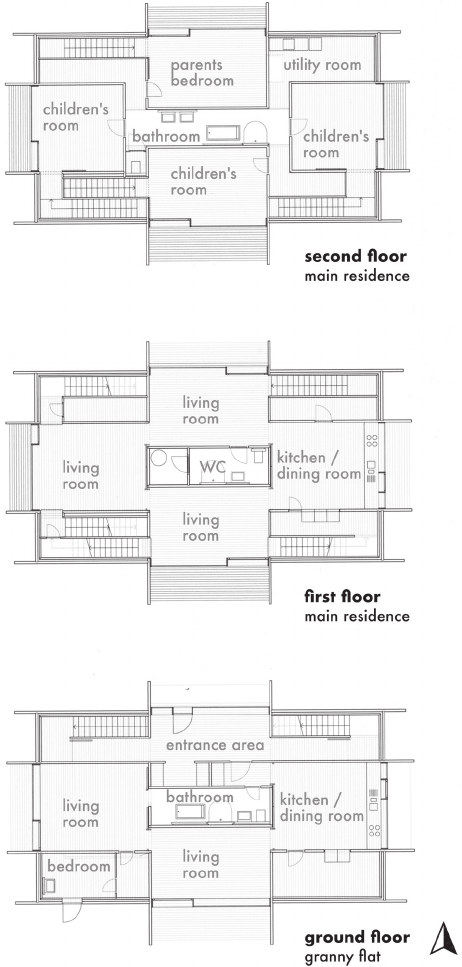

The granny at on the ground oor consists of three large

main rooms that merge into one another, a bathroom in the

Fig. 8. Jenaz (Switzerland) with Peter Zumthor’s Luzi House

in the background (photo by H. Schiefer)

Il. 8. Jenaz (Szwajcaria) z Luzi House Petera Zumthora w tle

(fot. H. Schiefer)

centre, as well as one ancillary room in the south-eastern

and two in the south-western tower. The arrangement of the

interior spaces is uid. As with most of Zumthor’s build-

ings, the three large windows in the main rooms celebrate

the view of the landscape and also create direct access to

the garden to the south and west (Durisch 2014a, 134). The

bathroom, which can be accessed from the entrance area of

the at and from the western living room, is enclosed on

all sides by wall surfaces and is therefore characterised by

a lack of brightness. On the south wall are terrazzo front

elements that extend the materiality of the oor into the

vertical and were designed as a continuous surface, but in

three graduated heights, corresponding to the bathroom

ttings of bathtub, shower, washbasin and toilet. Like the

wooden bathtub, the built-in wardrobes in the living areas,

which are customised to the house, also blend into the ow-

ing character of the rooms thanks to their shape, as they are

reminiscent of the movable room dividers known as shōji

in traditional Japanese architecture. The same applies to the

exibility in the use of these rooms, which was planned

from the outset. While the at initially functions as a guest

or granny at, as soon as the children grow up and one of

them wants to take over the upper house themselves, it is

to be occupied by the parents, for whom it is to serve as

a retirement home like a smaller house built on a farmstead,

also called a “Stöckli” in the region, where they would nei-

ther have to give up their existing ties to their village nor

use up more land (Hönig 2004, 26).

The main living area is located in the upper house,

which shares an entrance area with the granny at on the

ground oor and can be reached from there via a staircase

located in the north-east tower, while the staircase opposite

this, which can be accessed on the north-west side, leads

to the basement with adjoining garage, which is planned

on two levels and contains storage and pantry rooms. Both

staircases are designed in such a way that they cannot be

seen from the entrance area and can only be accessed af-

ter a 180° turn. The transition to a new living area on the

upper oor, marked in this way, is further emphasised by

the change in materiality of the suboor from the polished,

dark terrazzo to a lighter wooden oor. As the staircase